The development of the Package Insert (PI), also known as the Product Information, Prescribing/Prescriber’s Information, or simply “the Label,” is a long, complex process typically managed by a regulatory professional. It is a collaborative document, incorporating contributions from chemistry, toxicology, medical/clinical, biostatistical, writing, and regulatory professionals. Drawing from experience on a recent project, I would like to focus this installment of Protocol to Package Insert on the derivation of the clinical safety data that appear in the PI.

Many regulatory medical writers never have the chance to work on a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologic Licensing Application (BLA). This is explained by the fact that more than 90% of experimental treatments do not offer an appropriate benefit-risk profile. As a result, even experienced regulatory writers may never have the opportunity to contribute to the creation of the Package Insert (PI), the summary of the known properties and intended uses of a treatment. The development of the PI, also known as the Product Information, Prescribing/Prescriber’s Information, or simply “the Label,” is a long, complex process typically managed by a regulatory professional. It is a collaborative document, incorporating contributions from chemistry, toxicology, medical/clinical, biostatistical, writing, and regulatory professionals. Drawing from experience on a recent project, I would like to focus this installment of Protocol to Package Insert on the derivation of the clinical safety data that appear in the PI.

First, a bit of history. A very long time ago, just about everything you needed to know (or what was known) about a product was, literally, stuck on the outer label of the bottle, tube, or vial. As regulations and guidances demanded that more data be presented, the data were moved to an insert within the packaging of the product. Over the decades, the PI has grown in length and complexity. In the fall of 1966 the United States Congress passed the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act, requiring all consumer products in interstate commerce to be “honestly and informatively” labeled. Currently, the regulations governing PI content are presented in the 2006 Physician Labeling Rule (PLR), put forward by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In 2013, the FDA followed up with additional guidance for addressing these requirements in Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biologic Products – Implementing the PLR Content and Format Requirements.

The primary goal of the PI is to provide healthcare professionals with enough information to make treatment decisions, and monitor and advise patients. One of the most important considerations in this process is evaluating acceptable safety boundaries. This information is detailed in the section of the PI known as Adverse Reactions, or ARs. An AR is defined as an undesirable effect reasonably associated with the use of a product. In order to identify potential ARs, clinical trials collect adverse events (AEs), defined as any undesirable event that occurs in conjunction with the use of a product, whether or not product related.

So how does a sponsor determine whether an AE might actually be an AR? There are many considerations; among them are the timing of the AE relative to dosing, the effect on the AE of dechallange and rechallange (stopping, restarting) the product, and similar findings in other drugs in the same class. Depending on the number of subjects in a single study, potential ARs may be suggested; however, it is usually necessary to pool safety data across multiple studies within the clinical development program to properly assess whether an AE could be related to use of the product.

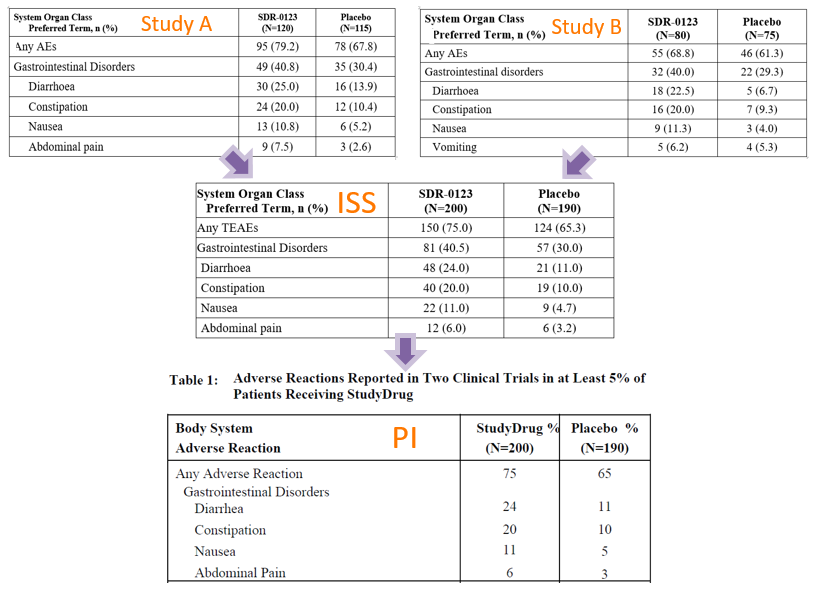

The Integrated Summary of Safety (ISS; usually only for US FDA submissions) and/or the Summary of Clinical Safety (SCS) compile safety data across studies for assessment. The premise is that the more data points available, the more likely a true reaction or effect will be observed. The table of ARs presented in a PI usually shows, in percentage of subjects, the suspected ARs of a product. Of course, we must keep in mind that safety data from clinical trials represent effects found in only a small fraction of potential users, in controlled situations. Consequently, ARs first presented in the PI are always considered potential. Over time, as a drug or biologic becomes more widely used in the greater population and/or more research is done, the nature of ARs becomes more certain. The following images show the derivation of the ARs presented in a PI from the ISS submitted in the NDA, and, in turn, from the Clinical Study Reports (CSRs) of the pivotal trials in the development program. Notice that in Study B, the AE ‘vomiting’ made the 5% occurrence cut-off determined to be meaningful in these studies. However, once data were pooled with the data in Study A, vomiting did not make the 5% cut-off. In the reverse situation, ‘abdominal pain’ was not so prevalent is Study B but was prevalent overall, in the pooled data.

This first installment of Protocol to Package Insert has provided a basic look at how safety data collected during clinical research become part of the product information available to healthcare professionals and consumers. In the next installment, we’ll review the path of efficacy data from the endpoints outlined in a clinical protocol to the results presented in the PI. Stay tuned!